Ten years ago this winter, I’d set a solid footing, grasped my life firmly at the root with each hand, and pulled myself out of my marriage. The momentum from the strain will bring me to Yasodhara Ashram. I quit my job and, on May 10, 2010, stepped into the unknown.

Nine years ago and I have graduated from the Yoga Development Course and the Hatha Teacher Certification. I am saturated with love and gratitude. I have wrung myself through thousands of hours of spiritual practice. I did not think that this depth of happiness was possible, borne out of the degree I understand and release my detrimental conditioning, my self-created pain. The deepest call of my heart is answered; I have found my spiritual home.

Eight years ago I have lived at the Ashram for two years. I expand my capabilities, write down my dreams every morning, awake before six to walk, chant mantra at lunch, and sing bhajans with Cy, where I experience an intimacy that goes beyond touch or vibration. I facilitate the program I first enrolled in and teach in the YDC. I am the most current version of my best self.

Seven years ago and I am leaving the Ashram, full with deeper understanding and a network of support. I will go to Maine and live on a sailboat in the Atlantic with Cy. My first trip to a grocery store has me overstimulated. This will be an adjustment.

Six years ago, I move to Montreal from Maine. Boxes packed, shipped, and labelled. My first few days with only the essentials I bring on the plane: guitar, yoga mat, and altar items. My antique Saraswati, Maine’s parting gift to me found in a ramshackle flea market, blesses an empty apartment. Red tape trim now fills the space with the promise of a home. I glue a life together from pieces.

“Where are you from?” they ask. The ocean had just swept away shards of my heart from Camden’s inner harbour into Penobscot Bay and out into the Atlantic; the boxes themselves had travelled east from land so dwarfed by sky it bows flat in reverence; a Temple on a mountain cliff overlooking a lake holds the feeling of home, but a month later even that would change, as flames that were fought all night burned Yasodhara’s Temple roof. Where am I from? It is too complicated a question; then and always.

I take the shuttle to the downtown campus and shop at the organic co-op, trawl thrift stores for curtains, and walk through this gaping metropolis. I play bhajans on my guitar and cry. I fall asleep with french words I do not know on repeat in my head, snippets of conversations I’ve heard that day, a glimpse into other realities.

Five years ago, my favourite East Coast Contra Dance band, Perpetual e-Motion, comes to Montreal. They fill the hall with lines of bodies, swirling in perfect rhythmic time, sustained by the notes of the didgeridoo.

Contra dance makes me feel alive. I am a dervish spinning wildly to the beat. This is a place not wrought with the social politics I experience as an Anglophone in a Francophone culture, this is a place where I can feel free. We switch partners seamlessly through each dance in the same way I see my colleagues change languages. I can lose myself in the dance in a different way that I am lost in conversation.

I bike home, my entire being cooled by sticky sweat meeting Montreal’s spring air to the Maison de l’amitié, a community house where I share three fridges and two wings with my eight roommates.

Freshly graduated, I start working downtown at the magazine. My office doesn’t have a window, but I can still see my hair blowing in the wind as I commute to work on the boulevard De Maisonneuve bike path.

I play the piano every day, cycle through the record collection, and interview and write about Olympians, award-winners, and artists. I am thrilled when my freelance pitches are accepted in national publications. I am too busy to become fluent in French. The burden of city life wears on me.

Four years ago, my home is my precious tent. Carried on my back, it is with me as I hitchhike across New Zealand. I love the nights when it is where I sleep, thin porous screens the only boundary between me and the outside. I want to breath New Zealand in. I want to lay my body on its earth. I always forget to bring enough drinking water to these makeshift solitary roadside camps of mine.

I stay for a month at Wilderland. My heart sings in this community as I forage the gardens for meals. My life is music, dirty bare feet, flowing clothing, and possibility.

Late at night we bring shovels to the beach for low-tide and dig a shallow tub in volcanic-heated springs. I pull myself out again and again to step into the ocean’s wet. In midnight’s dark I see outlines of walls push forward. Waves crash their coolness onto me. I hear the voices and laughter of my friends through the sea mist somewhere on the shore. I am naked and alone in the ocean. I am free.

I walk the grassy path back to my tent each night, stopping at my favourite natural bathroom spots alongside the trail. I am made for this open-air life. For these heaps of feijoas, a sweet and sour fruit that is everywhere. For this river that rises and falls with the sea. For early morning moon gazing through ferns and pink.

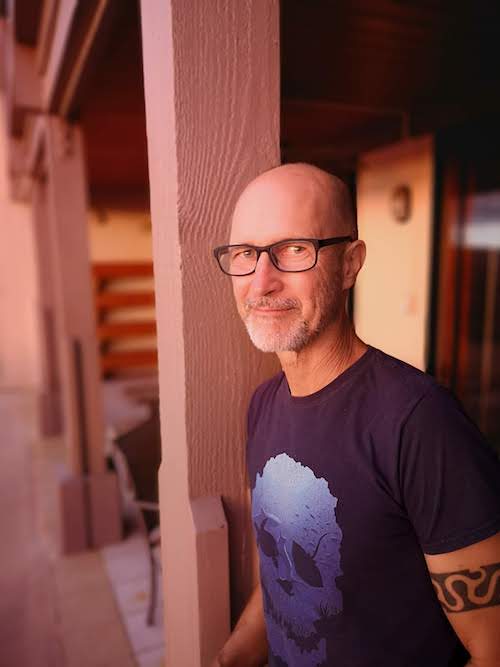

It’s springtime in the Northern Hemisphere and Rob has died. I’m home at Yasodhara in the mountains and we’re rebuilding the Temple of Light. More pieces of it are assembled each day. I stand in the centre of arcing lines and meet him there. He knew how much it meant to me. He watched from across an ocean bulging at the equator as it rose from its own ashes.

My own dark has been overpowering me. I’m struggling under its weight and I can’t get air. I want to feel the light again. I do not do much teaching.

His death is my catalyst and now I have small white pills with every breakfast and dinner. I start to feel the fog lift as bees buzz in fresh cherry blossoms. My brain transforms itself and new synapses grow. Thoughts of joy and creativity return. I’d been gone and now I am returning.

The Temple has windows now to keep out the cold. The fragile candle on the altar of my heart is safe from the breeze. We are being rebuilt together.

Two years ago I’m on the ferry crossing Portsmouth Harbour. I’m meeting Swami Sukhananda for dinner before we each take a train to different parts of the country. She’s been doing her yearly European tour and we’ve just had a weekend workshop at Lisa’s studio. My blissful and bleary state matches the incoming fog.

I’d met Lisa at 23. Despite the years gone past and our different life stages, my soul still feels stitched together in seeing her. Another human scattered across the globe that feels like home.

I take the evening train back to my new Brighton home and text with Phoenix, this man I still want to connect with. He’s 13 hours and two oceans away, our nights and mornings exchanged like confused moths frantically flying in daylight.

I work 14-hour shifts and wear my shoes through their soles. They fall apart on ancient barnyard stone that’s been converted to this wedding venue. It’s like every English fairy tale I’ve ever read.

My family decides to spread my grandfather’s ashes in the arctic in the summer. I’ve been waiting over ten years for this trip. I cancel my interview with the NHS for a communications job, and spend the remaining weeks before my return to Canada going to hot yoga, sleeping entire days away after weddings, and walking through cemeteries. England is cold. England is far away. England is not where I want to be.

I’m on a beach in Hawaii. I’m fighting a fever and have taken enough over-the-counter medicine to convince myself I can make something of this vacation.

The American government has let me into their country for exactly ten days maximum. I took a stack of paperwork proving my ties to Canada: job, house, commitments, and reference letters. After enough hours at the border to almost miss my flight, they let me through. When I’d tried to come in October, I was not successful.

I’m still in touch with Phoenix. I’m here to celebrate his birthday and to see in-person this man I attempted to spend another winter with before being thwarted by border control.

Our monogamously casual, mostly long-distance relationship has weathered a year-and-a-half. He’s come to Canada at least four times, each visit wildly different, their only consistencies the fraught first days while we get used to one another again and always get through to the other side.

I wonder what I’m doing on a lava rock in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. I fly away, back to my precious mountain town where I walk the same path every day at lunch. I clutch my phone to text this man who is so far away. I wonder what I’m doing on this lake shore in the middle of a mountain range.

Elephant Mountain rises behind me as I walk up the sidewalk of steps slowly to not lose my breath. Kootenay Lake glimmers in the sunshine. Horse chestnut flowers bloom, their petals falling at my feet. I do not see any of this. I see his face on the screen of our video call. I see our persistence. My own grasping, a hollow, faltered reaching to connect.

The world changed and everything in my life is uncertain. He holds me as I sob. “I don’t exactly know why I’m crying,” I say, muffled into his neck. Vibrations of sadness wrest out of my heart, finally given their chance to move through me.

We’d spent another winter together in Hawaii, but this time I can’t pretend to want the life he lives that he is not ready to say goodbye to. We left his communal home that I cannot accept for a vacation rental in the rainforest, a decision bathed in a pool of love that threatens to dry up. I measure my goals against the current world crises and re-valuate our two-and-a-half-year game of relationship chicken.

The sobbing shifts boulders inside of me. I watch the ocean pull itself back and reveal the same. Underneath, I find a familiar pea, one I know well and thought I’d fully digested and discarded years ago, I don’t believe I am worthy of love. The wave crashes onto newly exposed rock.

I’ve been running on auto-pilot. My heart has atrophied with neglect. I have forgotten how to connect with myself, anything else, him. I miss my grandmother.

My visa for this country expires in one month. I do not know where I will go, what I will do, how I will get there, or if there will be a “we”.

I’ve been rededicating myself to spiritual practice, upping the amount of time I spend in contemplation, adding and re-adding moments of the sacred to my day. All this light shows me the dark places. I sweep out the dust it reveals with my left hand, while my right tries to reach into a bin of engrained patterns of codependency to scatter more. I do not quite know how to stop spreading the dust.

I keep praying. I keep asking. I keep crying with my heart alight, revelling in the massage these sobs give her. She vibrates with a deeper joy than this upturned world can provide. She reminds me that I know what love is, that I know the pathway back.

I want to wipe away the past and rebuild. I want to watch these polarizing societal structures crumble. I want to see what Siva leaves in His wake.

Reflected light filters into my eyes and I imagine I can differentiate between each photon as it passes information to my brain. How can it be a particle and a wave? How can it alter depending on the way we look at it? My imagination shows me light’s true nature as my lived reality tries to make sense of love’s true nature.

I am still here, suspended among both of them, remembering to breathe.